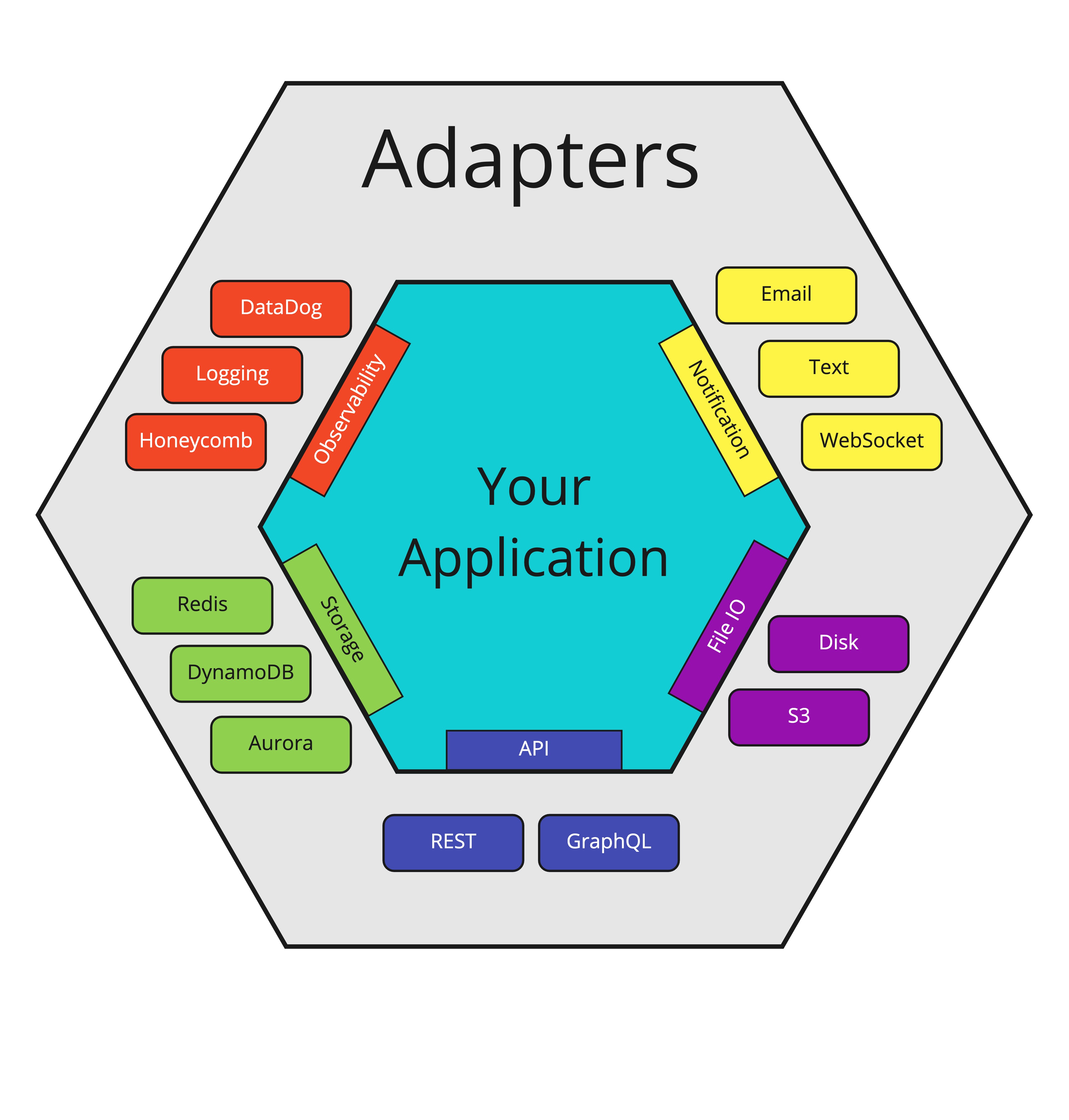

Hexagonal architecture (or ports and adapters, depending on who you ask) is a software architecture pattern that concerns itself with the separation of application logic from inputs and outputs by lifting them from the application itself, to the “edges” of the code base.

An example

Let’s say you have an application that needs to send an email to its users. To do that, your code might look something like this:

interface User {

username: string;

}

const sendUpdateEmail = async () => {

/**

* Sends an update email to all users.

**/

const response = await fetch("/api/users");

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error("Invalid response");

}

const users: User[] = response.data as User[];

// we're using AWS' Simple Email Service

const email_client = new SESEmailClient();

const emails = users.map((user) => {

email_client.sendUpdateEmail(user)

});

await Promise.all(emails);

}

sendUpdateEmail();

Now this looks all fine and well, it does the job. But it’s quite difficult to test without mocking fetch and SESEmailClient, and if we wanted to change either of these things in the future (maybe we’d fetch the users from Aurora, or a DynamoDB table, or swap our email client to Mailchimp), we would need to modify this code and rewrite our tests. Which, is a pain.

To be more specific the above has several Single Responsibility violations, and we would describe it as having low cohesion. This function is responsible for knowing HOW to gather users and controlling errors, as well as WHICH email client we’re using.

Secondly by mocking fetch and the SESEmailClient, we’re committing the sin of mocking things we don’t own, which couples our tests to third party libraries!

To improve things, we might consider moving logic out of this function so we can decouple the behaviour.

interface User {

username: string;

}

const getUsers = async (): Promise<User[]> => {

const response = await fetch("/api/users");

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error("Invalid response");

}

return response.data as User[];

}

const sendEmails = async (users: User[]): Promise => {

const email_client = new SESEmailClient();

const emails = users.map((user) => {

email_client.sendUpdateEmail(user)

});

return Promise.all(emails);

}

const sendUpdateEmail = async () => {

const users: User[] = await getUsers();

await sendEmails(users);

}

This has made sendUpdateEmail much easier to read, we can now clearly understand what it’s doing and it has a reduced number of responsibilities. What about the other things I mentioned? Is it easier to test? Well, no, we still need to mock these functions, but we’re no longer mocking things we don’t own. What if we need to change their behaviour? Well now we only need to change it in one place. The mocked tests will continue to function, we’ll just need to replace the tests we had for getUsers and sendEmails.

Sounds like we’re done!

But what if wanted different behaviour in different environments? Maybe engineers should just send emails to a log file, rather than to actual users?

Say hello to Ports and Adapters

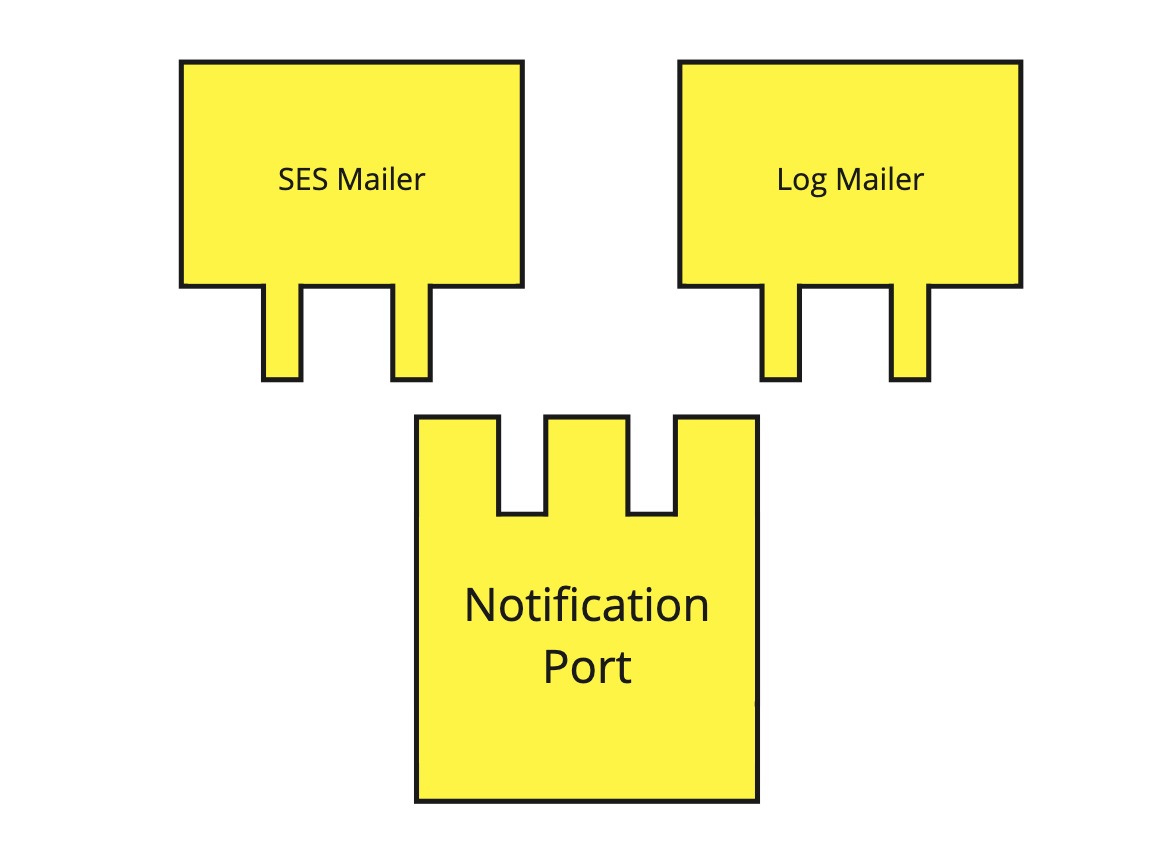

A port is the definition of some kind of behaviour. An adapter is the concrete implementation of a port that is actually executed.

By having our code rely on interfaces, we can not only alter the behaviour in different environments or different function calls, but also modify it easily as our systems grow.

interface User {

username: string;

}

// in reality these would usually not be suffixed with Port, it's just here for

// clarity

interface UserPort {

getUsers: async () => User[]

}

interface MailerPort {

sendUpdateEmail: async (users: User[]) => void

}

const sendUpdateEmail = async (userRepo: UserPort, mailer: MailerPort) => {

const users: User[] = await userRepo.getUsers();

const emails = users.map((user) => {

mailer.sendUpdateEmail(user)

});

await Promise.all(emails);

}

But how do we call sendUpdateEmail now? Excellent question.

const HttpUser: UserPort {

getUsers: async (): User[] => {

const response = await fetch("/api/users");

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error("Invalid response");

}

return response.data as User[];

}

}

const SesMailer: MailerPort {

sendUpdateEmail: async (users: User[]) => {

const email_client = new SESEmailClient();

const emails = users.map((user) => {

email_client.sendUpdateEmail(user)

});

return Promise.all(emails);

}

}

const LogMailer: MailerPort {

sendUpdateEmail: async (users: User[]) => {

const emails = users.map((user) => {

console.log(`Sending update email to ${user.id}`);

});

return Promise.resolve();

}

}

// Swap the mailer that's used depending on the environment we're in

// (There are cleaner ways to do this, but it's just a demo!)

const mailer = IS_PRODUCTION ? SesMailer : LogMailer;

sendUpdateEmail(HttpUser, mailer);

Notice how the mailer we use varies depending on if we’re in production or not? Our function that sends the update email has no idea that this has occurred, it sees the exact same behaviour regardless of what’s actually happening within the adapter.

Hold on, this seems like a LOT.

How have we taken a ~20 lines of code and ended up with over double?! Isn’t this overkill?

Like any architectural decision there are tradeoffs, and understanding those is crucial in knowing if this trade off is worth it.

Ports and Adapters promotes the creation of modular and easily testable code, which in turn improves the readability of code and helps create more maintainable codebases. If that’s something that sounds appealing to you, then they’re probably worthwhile. If you’re just hacking something together in perl however, you’re probably okay.

A few years ago Netflix wrote a post on the usage of this pattern and how it helped them swap reads from a RESTful API to a GraphQL based one, check it out!