Before we can understand what a Transactional Outbox is, it’s important to first understand what a vanilla Transaction is. I may write another ‘what is’ article on those in a more detail, but essentially a transaction is an “all-or-nothing” guarantee. You perform multiple mutations on a system, and either they are all applied successfully, or the system “rolls-back” to the previous state and it’s as if nothing happened at all.

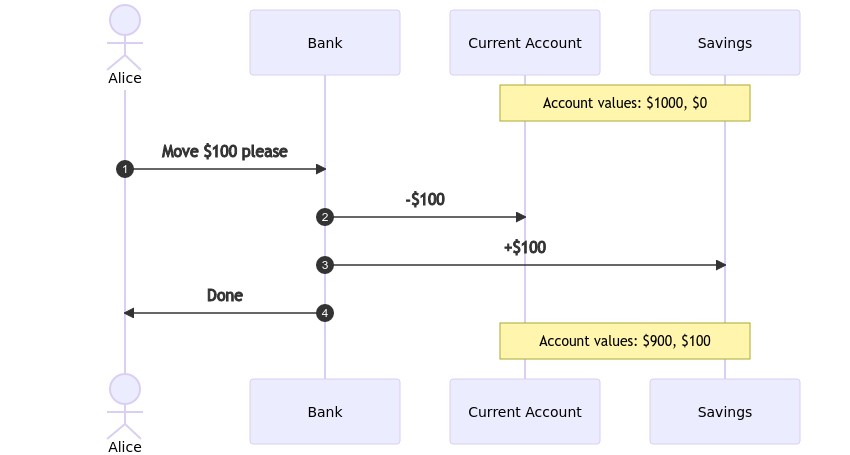

For example, let’s say Alice has a current account at a bank with $1000 in it. She’d like to begin a savings account so she opens another account and moves $100 to it from the first. As a sequence diagram, it might look something like this:

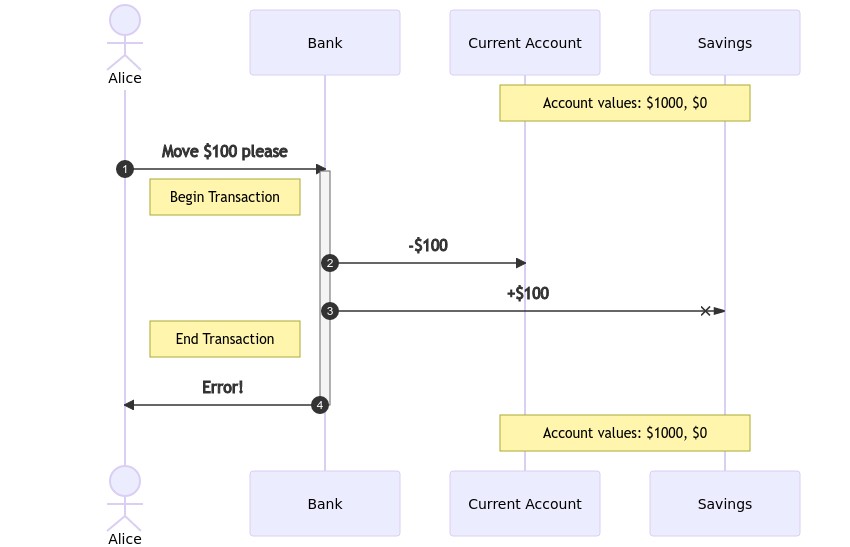

But what happens if step 3 fails? The server catches fire, the network is down or someone leans on the power button? Any number of things could happen which would result an in inconsistent state. Alice would seem to have lost money, with no way to recover!

Now if the order of these transactions were reversed, Alice probably wouldn’t mind too much, she’s gained an extra $100 for free! As it stands however, I think she’d be quite annoyed. To solve this, we wrap the two operations in a transaction.

and the code might look something like this:

def move_money(from_account: str, to_account: str, amount: int):

conn = psycopg2.connect(dsn)

cursor = conn.cursor() # starts the transaction

cursor.execute(

"UPDATE SET amount=amount + %n WHERE account_id=%n",

[amount, to_account]

)

cursor.execute(

"UPDATE SET amount=amount - %n WHERE account_id=%n",

[amount, from_account]

)

cursor.commit() # commits the transaction

The are much nicer ways of doing the above with context managers, I just wanted to be explicit.

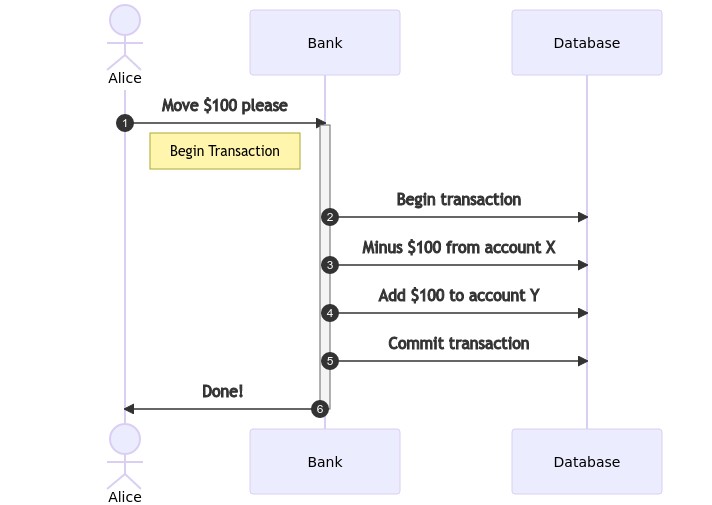

Both of these accounts are within the same database, so what we’re doing is:

What’s important to understand however, is that any of the steps that speak to the database can fail, including the final commit itself. No matter what happens however, the database ensures that if you don’t perform the final commit, no changes occur.

Well that’s quite nice. We’re relying on our data store’s ability to provide transactional safety… but what happens if you need to perform updates across distinct systems where such this isn’t guaranteed? Maybe we’d like to send a notification that the operation was successful - something that is outside of our data store? We’d only want to do that if the operation actually succeeded!

Enter, the transactional outbox.

Multi-phase operations (sending a notification)

Performing multiple actions within the confines of a transaction is nice easy to do, but as soon as we step outside it we are open to problems. It’s important to remember when designing systems like this that any operation that can fail, will eventually do so. How will your system recover? If we wanted to send the notification inside the transactional block, but the transaction fails to finish, then we would have sent a notification but the transaction would have rolled back: the user would be told a change had occurred when in reality it wouldn’t have.

Any operation that can fail, will eventually do so

Secondly, it’s important to ask ourselves the importance of these operations in terms of their consistency. When moving money from one account to another, it makes sense for this to be strongly consistent, that both changes are performed simultaneously. But does the notification? Can that happen after? It seems that it doesn’t really matter too much when the user receives the notification as long as it’s within a few minutes, just that they do so after it’s occurred, it can be eventually consistent.

Sending a notification is very different to storing data in a database, what would happen if we were to attempt to send one directly?

def move_money_and_send_notification(

from_account: str,

to_account: str,

amount: int,

user: str

):

conn = psycopg2.connect(dsn)

cursor = conn.cursor() # starts the transaction

cursor.execute(

"UPDATE SET amount=amount + %n WHERE account_id=%n",

[amount, to_account]

)

cursor.execute(

"UPDATE SET amount=amount - %n WHERE account_id=%n",

[amount, from_account]

)

# let the user know their money has been moved

send_notification("Money moved!", user)

cursor.commit() # commit

The above example looks like it’ll work, if we fail to send the notification the the transaction will error, and roll back. But what if the commit itself fails? In this case we’ll have sent Alice a notification that the money has been moved, but nothing will have actually changed. Which is confusing, and annoying.

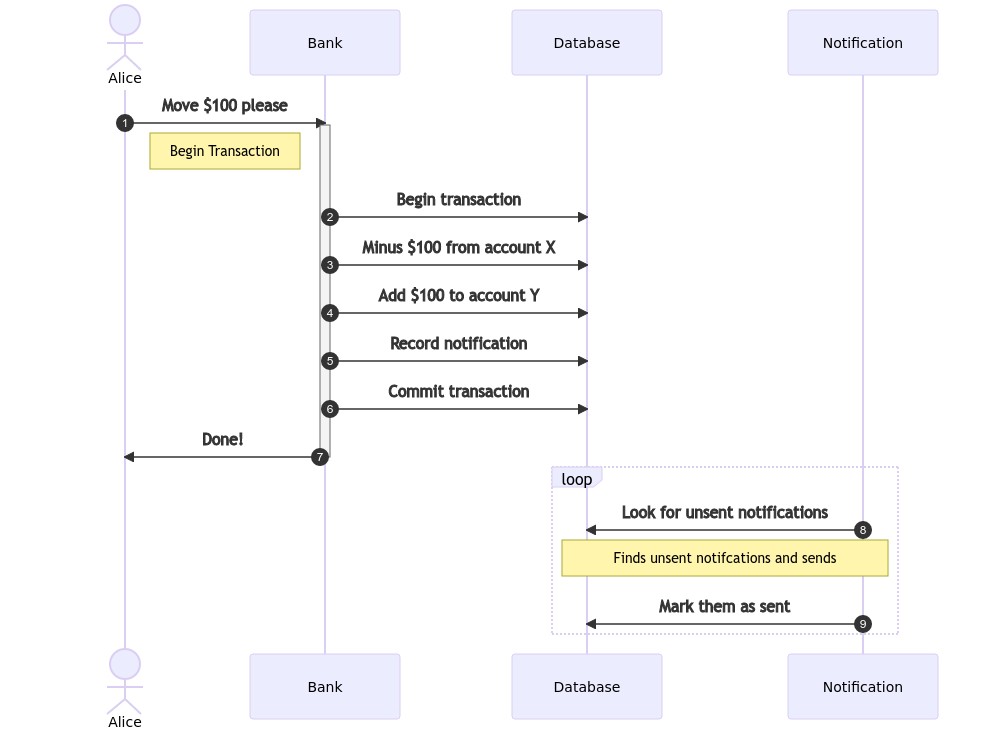

Instead, what if we recorded the fact a notification needed to be sent, and another system looked for them independently?

or as code:

def move_money(from_account, to_account, amount, user):

conn = psycopg2.connect(dsn)

cursor = conn.cursor() # starts the transaction

cursor.execute(

"UPDATE accounts SET amount=amount + %n WHERE account_id=%n",

[amount, to_account]

)

cursor.execute(

"UPDATE accounts SET amount=amount - %n WHERE account_id=%n",

[amount, from_account]

)

cursor.execute(

""""

INSERT INTO notifications (user, message, sent)

VALUES ("Success!", %s, False)

""",

[user]

)

cursor.commit() # commits the transaction

Then an independent operation polls this table looking for notifications to send (you might call this a message relay):

def find_and_send_pending_notifications():

conn = psycopg2.connect(dsn)

cur.execute(

"SELECT id, message, user FROM notifications WHERE sent=False"

)

sent_ids = []

for row_id, message, user in cur.fetchall():

send_notification(message, user)

sent_ids.append(row_id)

cur.executemany(

"UPDATE notifications SET sent=True WHERE id=%s", send_ids

)

Great! We’ve decoupled the two operations while guaranteeing that the second one will occur, it just won’t occur straight away. The downside in the above example is of course that if we fail to mark them as sent then we’ll repeatedly notify the user. This is an example of at-least-once delivery.

And there we have it! A transactional outbox is a pattern used to guarantee that operations performed on distinct services will occur.