In the last post we had an introduction to the problem we were trying to solve, and a brief look at the simplest possible solution generating technique for it, to guess randomly. Let’s see if we can do better, but first I’d like to point out some concepts in our code design the encapsulate parts of the problem.

As a reminder, the constraints we’re dealing with are:

- The sales person must visit every city

- The sales person can only visit each city once

- The sales person must return to their start location

How have we represented these in our algorithm thus far? The first is that the Solution itself contains a list of all the cities to be visited, and any Trip is built from that list in its entirety. As such, we have made it impossible to not visit a city.

The second is in the Trip object itself. We could represent the nodes that we visit as a graph, with edges between nodes that are being visited. If we did this however, we would have a more complex data structure AND possibly allow for nodes to be more inter-connected than our constraint allows. As it stands an array of cities shows the order in which they are visited, without the possibility multiple routes to the same place.

And lastly, this is captured in the objective function itself. The total cost of the trip is the distance between the cities, plus the distance from the final city back to the first. Lovely!

These design decisions are important, as they massively impact the type of solution that we can represent. You might be thinking that this representation matches the constraints well, and the decisions reduce software fragility by making entire classifications of bugs impossible (e.g. you physically cannot represent multiple routes to a city), and that’s true. But in doing so we remove the ability to relax these constraints, and have temporarily infeasible solutions that we later fix. But, more on this in a later post!

Climbing up that hill

We’ve seen that we can easily create a solution that is totally random, where do we go from here? Well, now that we have an initial solution, what happens if we begin making changes to it? As we’ve said above, our current representation doesn’t allow for invalid solutions, just different degrees of bad ones. So by taking a solution and applying a move to it, we can create a new one. And if it’s better, we’ll simply keep it. This is called hill climbing, while this type of perturbation to the solution is called a local search. We’re starting from one solution and applying a small change to it and ending up relatively close in the overall solution space.

So what kind of moves are we talking about here? What can we do? Well, a non exhaustive list might include things like:

- Randomly move a city

- Randomly swap two cities

- Randomly move a sub route

- Flip a sub-route

- Take a random city, and try every location

- Take a random sub-route, try every location

- (or anything else you can think of)

There’s many we could do! I’ve listed them here roughly in order of their complexity to perform, and impact on the search. For now however, and to illustrate the power of hill climbing, let’s implement the first move.

Now we don’t want to expose too much of our Solution internals to the outside world. Ideally, this class could provide mechanisms for performing modifications, but not the modifications themselves. So, we want to randomly move a single city. Looking at the list, we can see that moving a single city is a simplification of another move there, moving a sub-route, so I decided to extend the solution class with the following:

class Solution {

...

moveSubRoute(fromIdx: number, toIdx: number, n: number): Solution {

let newRoute = [...this.trip.cities];

newRoute.splice(toIdx, 0, ...newRoute.splice(fromIdx, n));

const trip = new Trip(newRoute);

return new Solution(this.cities, trip);

}

}

and the move to for a single random city is:

const moveCity: Move = {

apply(solution) {

const a = randomInt(solution.cities.length);

const b = randomInt(solution.cities.length); // may pick the same index!

return solution.moveSubRoute(a, b, 1);

}

};

Nice and simple. But can it really do that much? We’re still just guessing randomly aren’t we? And how do we know when to stop?!

As we’re exploring our solution space in a non-deterministic way, we have to configure the algorithm itself as to when to stop. It cannot know when it’s done ahead of time, unless it evaluates every possible move it can perform. With that in mind then, we need to extend our Runner to include a notion of a configurable stop:

type StoppingCriterion = () => boolean;

/**

* Will return true n times

*/

const fixedIteration = (numIterations: number) => {

let iterationCount = 0;

return () => numIterations === iterationCount++;

};

class Runner {

run(

cities: City[] = ATT_48_CITIES,

construction = RandomConstruction,

shouldStop: StoppingCriterion,

move: Move,

initialSolution?: Solution

) {

const emptySolution = Solution.default(cities);

let bestSolution = initialSolution || construction.apply(emptySolution);

while (!shouldStop()) {

const candidateSolution = move.apply(bestSolution);

if (candidateSolution.cost() < bestSolution.cost()) {

bestSolution = candidateSolution;

}

}

return bestSolution;

}

}

Then to execute we would perform the following:

runner.run(

ATT_48_CITIES,

RandomConstruction,

fixedIteration(1000),

moveCity

);

Neat, but what does this actually do for us? Let’s try it out and see!

If you click around a little you may notice a few things:

- it quite quickly makes large improvements

- the better it gets, the less likely it is to improve

- clicking a single move often doesn’t change anything at all

- how good it can get varies a LOT. (closest I got to best was around 300)

What I find really fascinating about this is that the algorithm often produces solutions that are not only quite good, but are often very different from what you or I may intuitively predict. And this is just with a single, random movement! Not only that, but it does so very, very quickly. Hill climbing rocks.

What if we’re climbing the wrong hill?

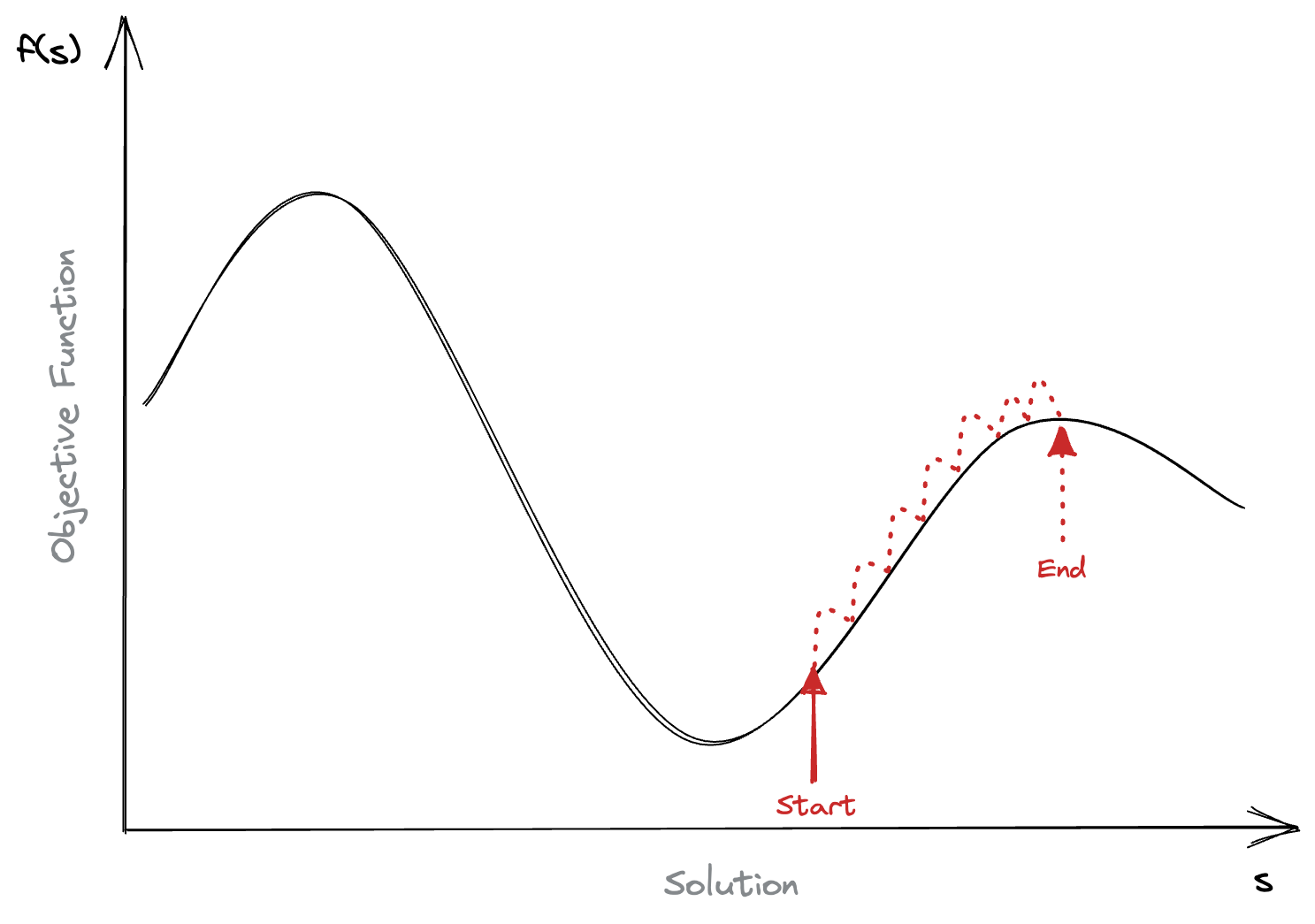

This is the catch of hill climbing. It’s an intensification process, and as such will become trapped in local maxima. In the figure above we’d never escape the local maxima, as we’d need to make the solution worse before it could get better.

There’s multiple ways that this can be approached, one might be to include a diversification process, something to perturb our solution away from the maxima. While another may be via construction. Can we build a better initial solution to explore? Can we find a better hill to start on?

Both excellent questions, and will be covered in future posts!