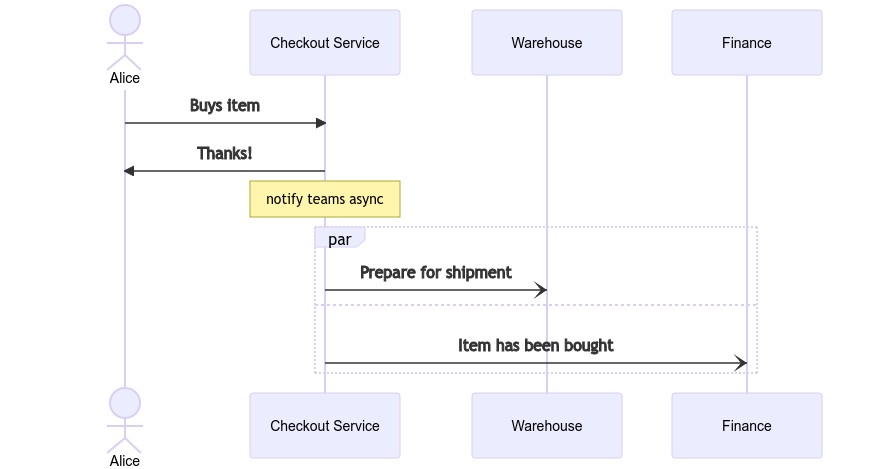

When thinking about systems, we often think about the guarantees that those systems represent. The guarantees that we require are usually a reflection of the behaviour that we expect the system to reflect. For example, we might require that when a user buys a product, the warehouse and finance team are made away.

(Arguably this isn’t the best customer experience, letting the finance team know about this purchase may not be critical to the customer’s ability to purchase something, and so it being a blocking operation may not make much sense, but hey, run with me here.)

What would happen if the call to the warehouse were to fail? Or the system lost power, losing state? Could we be sure that we’ve sent an item for processing? Or that we can accurately report on our sales?

The answer of course, is no. Our system has very little durability whatsoever.

The WAL

A Write-Ahead Log is a durability mechanism. By introducing an append-only log file, and adding a constraint to our system that transactions are only considered committed once they are in this file, we’re able to recover from a host of failure scenarios.

As the system comes online, it can reply all the events in the WAL to ensure that it is up to date. As the system grows however, this can quickly become a bottle neck, and so we might introduce a “low water mark” to track the latest record we’ve processed, or segment the log itself so we only need to rerun changes from the past few hours.

This may sound a lot like event-sourcing, but one of the key differences is that where event-source applications can reconstruct state at any point in time by replying events, a WAL is designed to be pruned. All records prior to the “low water mark” can be removed, likewise previous segments that have been processed.